The Carolina Neurodevelopmental Disabilities Project

The Carolina Neurodevelopmental Disabilities Project (CNDP), directed by Dr. Molly Losh, is a group of multidisciplinary studies investigating the speech, language, and social-behavioral profiles that define different developmental disabilities. Specifically, our studies focus on autism spectrum disorders, fragile X syndrome, and Down syndrome and investigate the neuropsychological, genetic, and environmental features that may be associated with the behavioral and cognitive profiles of these different groups. Specific study goals include:

- To understand the different strengths and weaknesses in speech, language, and social understanding across different groups and over development.

- To define subtle language and neuropsychological profiles that may relate to the genes involved in autism and fragile X syndrome, among unaffected relatives, and trace their patterns of expression in families.

- To document the interactions between genes and environment in speech, language, and social development.

Courtesy of Molly Losh

Autism is a developmental disability involving language and social impairments, and stereotyped interests and behaviors. The etiology of autism is complex, but strong evidence points towards a genetic basis.

More information about autism and its causes can be found at the website for Autism Speaks, which is the nation’s largest autism advocacy organization: https://www.autismspeaks.org/

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the most common cause of inherited intellectual disability, caused by a mutation in the FMR1 gene. FXS involves characteristic appearance and behavioral features, including language and speech delays. FXS is also the most common known cause of autism.

For more information about FXS, please see the National Fragile X Foundation website: https://fragilex.org

Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability. It is typically caused by an error in cell division that occurs at conception, leading to an extra copy of the 21st chromosome (trisomy 21). Individuals with Down syndrome experience physical and cognitive developmental delays.

Additional information about Down syndrome can be found at the National Down Syndrome Society website: http://www.ndss.org/

Genetic Analysis

Molly Losh, Assistant Professor in Speech and Hearing Sciences and Psychiatry, describes her research in the genetics of Fragile X syndrome.

”Our studies include the analysis of DNA in order to identify gene-behavior relationships that may help us better understand the basis of the language difficulties experienced by individuals with developmental disabilities such as autism and fragile X syndrome.”

-Molly Losh PhD, Assistant Professor, Division of Speech and Hearing Sciences, Allied Health Sciences, and Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, and Director, The Carolina Neurodevelopmental Disabilities Project

The Importance of Family Trees

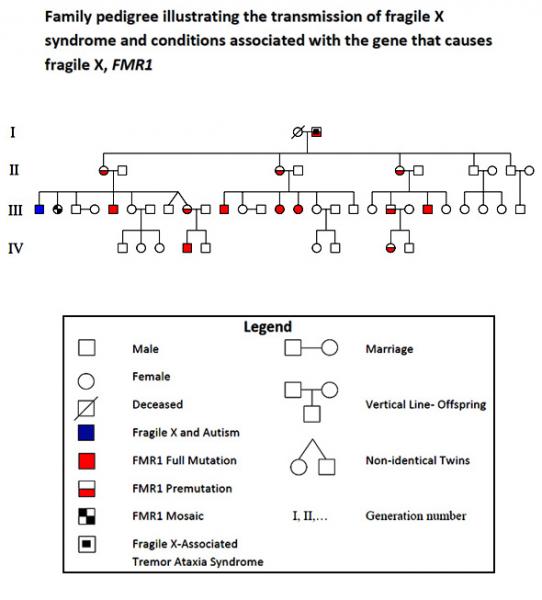

We use family trees, or pedigree drawings, to begin to trace genetic and clinical information throughout families. Pedigree drawings indicate which family members may be carriers of certain genes, and who expresses different clinical characteristics that may be associated with these genes, or otherwise important to consider. This example shows a family pedigree in fragile X syndrome, indicating which family members show different characteristics, as well as those who are carriers of FMR1 in its full and premutation states. (See pedigree drawing)

FMR1 was identified as the gene that causes fragile X syndrome in 1991. This gene controls an important protein expressed in the brain (FMRP). When the gene is fully mutated it shuts down and the protein is not expressed, leading to the clinical characteristics of fragile X syndrome. The gene can often be transmitted in its premutation state among relatives of individuals with fragile X syndrome. The premutation FMR1 has recently been associated with certain conditions such as fragile X associated tremor ataxia syndrome, and increased rates of depression, but it remains unclear whether it may be related to additional behavioral or neuropsychological characteristics. In our studies we examine links between genetic characteristics (related to FMR1 and other genes), and the language and social cognitive features that are measured in individuals with developmental disabilities and their family members.

DNA Collection

Courtesy of Molly Losh

Our research team collects DNA samples through venous draws or through finger pricks with a lancet. In the latter case, blood spots are collected and dried on cards, and then sent to the lab for DNA extraction. This display shows photos of the blood spot collection as well as the tools involved-a finger lancet, a special card for creating the dried blood spots, a distractor that is often used with children, and tubes that we use for venous draws.

Courtesy of Molly Losh

Courtesy of Molly Losh

Language Assessment

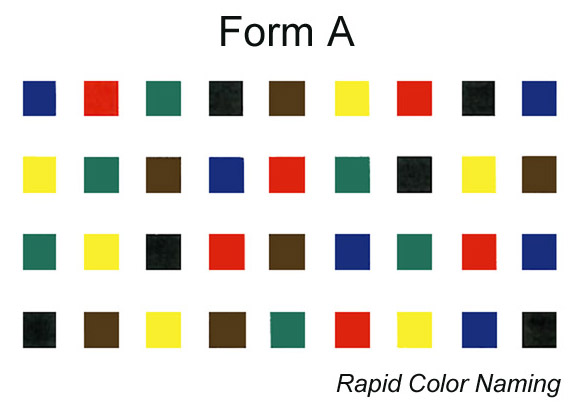

Rapid Automatized Naming

(Language processing and fluency task)

Language processing and fluency, as indexed by rapid automatized naming (RAN), taps such fundamental language skills as phonological processing and memory, articulation, and processing speed. For this task, participants are shown a laminated sheet with color squares and are instructed to name each as quickly and accurately as possible. Outcome variables include time to completion and number of errors. (See RAN stimulus on display, from the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, Wagner et al., 1999)

Frog, Where Are You?

(Narrative task)

Storytelling, or narration, is a sociocultural activity that allows us to organize and relate experiences in meaningful ways. Narrative ability draws upon cognitive, linguistic, and social emotional knowledge. Since each of these domains is impaired in autism and fragile X syndrome, narrative analysis can provide a rich source of information regarding such deficits. To assess narrative ability in our participants we use the book Frog, Where are You? (Mayer, 1969), which is a wordless picture book depicting a story about a boy and his search for a lost pet frog. Participants are first instructed to look through the pictures to familiarize themselves with the story and then are asked to tell the story to the examiner. Stories are analyzed for key linguistic mechanisms used to create coherent narratives. (See narrative stimulus on display)

Courtesy of Penguin Group (USA), Inc.

”Impaired use of language and pragmatic language in particular is a hallmark of both autism and fragile X syndrome. Language deficits can compromise all aspects of social interactions, impacting relationships with peers and adults at home, in school, and in the community at large.”

Courtesy of Molly Losh

Theory of Mind Tasks

Courtesy Molly Losh

Courtesy Molly Losh

Unexpected Contents

(False Belief Task)

False belief tasks measure children’s mental state awareness, and the understanding that beliefs involve representations of reality and so can be mistaken. False belief tasks were first introduced to the study of human development by Wimmer and Perner in 1983, and many variations now exist. In the unexpected contents task, an experimenter asks children what they believe to be the contents of a box that looks as though it holds candy (e.g., an M&Ms box). After the child guesses (usually) ”candy,” they are shown that the box in fact contains buttons. The experimenter then re-closes the box and asks the child what she thinks another person, who has not been shown the true contents of the box, will think is inside. By the age of 4 or 5, typically developing children are able to respond correctly, that another person will think that there is candy in the box. Prior to that age, children are typically unable to distinguish their own informed knowledge  state from another’s naive state of mind, and respond that another person will think that the box contains buttons.

state from another’s naive state of mind, and respond that another person will think that the box contains buttons.

The Rock-Sponge

(Appearance vs. Reality Task)

This task measures children’s ability to hold dual representations of apparent and real properties, or identities of an object. This skill is crucial for later developmental achievements such as the understanding that people can hold beliefs, thoughts, and emotions that are different than one’s own. Appearance-reality tasks, such as the Rock-Sponge task, were pioneered by John Flavell and his colleagues in the 1980s. In this task, children are asked what the object looks like (a rock), and then allowed to touch the object (actually a sponge painted o look like a rock), and asked which the object really is. By about the age of 4 years, typically developing children grasp the appearance-reality distinction and answer correctly. This understanding may be delayed in children with  This understanding may be delayed in children with developmental disabilities such as autism, fragile X syndrome, and Down syndrome.

This understanding may be delayed in children with developmental disabilities such as autism, fragile X syndrome, and Down syndrome.

Photos: Robert Ladd

Autism and Fragile X Syndrome

Autism and Fragile X Syndrome